The Macaulay Library started archiving photos from birders who add them to eBird checklists in 2015. Since then the library has accumulated more than 34 million photos of 10,350 species. The collection, Mike Webster, director of the Macaulay Library, says “is a gold mine for birders and researchers alike.”

New research out this week in The Wilson Journal of Ornithology highlights what can be learned by digging into the gold mine of photos in the Macaulay Library. Peter Pyle, staff biologist at the Institute for Bird Populations, examined more than 27,000 photos of eight different species of hummingbirds in the Macaulay Library. Pyle discovered the manner in which these eight species of hummingbirds replace their feathers, or “molt strategies,” that was not well-understood for these species. Pyle also used the photos to construct a primer that will allow biologists to determine the age of individuals in the hand and by examining photos.

Understanding molt strategies is critical to determining a bird’s age, which can help scientists estimate reproductive success and survival and thereby better understand the health of a population and habitat quality. Even though Pyle admits studying molt, “is rather boring—there isn’t a lot of drama there,” understanding when, where, and how birds replace their feathers has these important implications for conservation.

Blue-throated Mountain-gem Lampornis clemenciae

“Molt,” says Pyle, “is a very energetic and costly process for the birds, which leaves them vulnerable.” Replacing feathers can cost a bird more than a quarter of its body protein, so when it’s time to molt, birds need to find high-quality food and shelter. Until recently most species were thought to replace their feathers on the breeding grounds after they finished raising their young. But researchers at the Institute for Bird Populations found that many bird species replace their feathers outside of the breeding area.

“We need to understand where birds go to molt and protect the habitats that provide cover and nutritional needs when flight is impaired during molt so individuals can successfully replace their feathers,” says Pyle.

Photos in the Macaulay Library may be one way for researchers to identify where birds are molting their feathers.

Broad-billed Hummingbird Cynanthus latirostris

“Now almost everyone has a digital camera, so you can really study feathers in detail,” says Pyle. Museum specimens are useful for studying molt, he says, but ornithologists often refrained from collecting birds that were replacing their feathers because they were not in good condition. “Photographs in the Macaulay Library open up a whole new data set that goes way beyond what is easily acquired from museum specimens,” says Pyle.

The photos in the library can be used to answer many other questions as well, such as how what a bird eats influences its plumage. Pyle shared that photos in the Macaulay Library helped researchers determine that feathers of some Western Tanagers that were normally yellow or green were instead reddened. This was not because they were hybridizing with other tanagers, but because of the chemical signature in honeysuckle berries that the Western Tanagers were eating.

“There is a great potential to learn about a lot of things with images in the Macaulay Library,” says Pyle. Many of those great images are also used to illustrate Birds of the World species accounts, which Pyle helps revise and curate. Subscribers to Birds of the World can see great examples of how Macaulay Library images are used to illustrate very specific ages and plumages of birds.

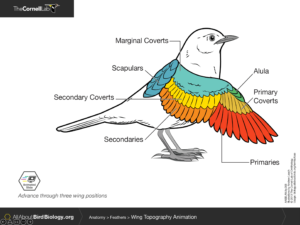

Pyle hopes to get the message out to bird photographers about uploading all of their images to the Macaulay Library, not just the beauty shots. “Don’t hesitate to take photos of birds in molt,” he says. “Even though the bird may not look spectacular, get as many photos as you can, especially of the bird with its wings open or tail spread—those photos are particularly valuable.” Pyle also recommends taking more photos of young and female birds.

Lucifer Hummingbird Calothorax lucifer

Reference:

Pyle, P. (2022). Examination of digital images from Macaulay Library to determine molt strategies: a case study on molts and plumages in eight species of North American hummingbirds. Wilson Journal of Ornithology