In March the world suddenly grew quieter as stay-at-home orders were issued to help stop the spread of COVID-19. And for many, the quieter streets made them take notice of birds, some for the first time, right in their own backyard. Interest in bird watching has grown more this year than at any time in the past. More and more people have started tracking the birds they see with eBird, adding valuable information that will help us understand birds where people live.

Others took advantage of the quietness to record bird sounds. In some parts of the world urban noises mask the sounds of nature, so much so that Rita Shrivastav, a bird watcher in India, told the Times of India, “You can hear so many different birds now.”

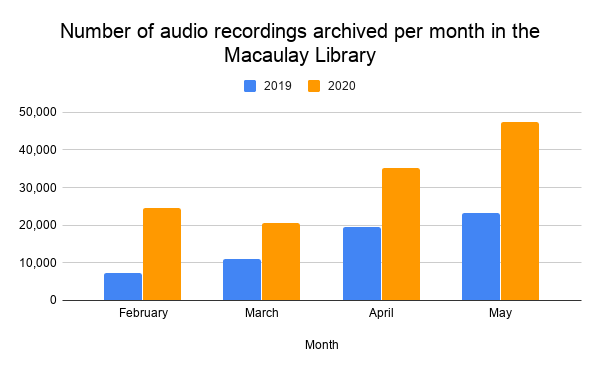

In the last few months the number of audio recordings archived with eBird checklists in the Macaulay Library has surged. Between March 1st and May 31st eBirders contributed more than 100,000 audio recordings. By comparison it took more than 70 years for the Macaulay Library to archive its first 100,000 recordings. In the month of May alone, contributors added nearly 50,000 new recordings.

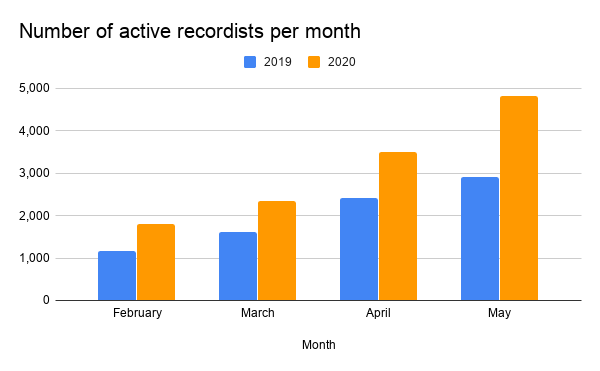

Not only are more recordings coming into the archive, more people are starting to discover the joy of recording. Nearly 5,000 people archived recordings in May 2020 and more than 1,000 (25%) of those people archived their very first recording. The Macaulay Library would not be where it is today without citizen scientists who have spent so much time and energy recording birds. The Macaulay Library now has more than 750,000 audio recordings representing 89% of the bird species on earth; all thanks to our dedicated community of birders and recordists!

We reached out to a few recordists around the world to learn what sparked their interest in recording bird sounds and how current events have changed how much and where they record bird sounds.

Hakimuddin Saify, from Chhattisgarh, India, has been recording bird sounds on and off for the last two to three years, but he says he never took it seriously. Now Saify has a dedicated recording unit and says, “recording is an integral part for me while birding! I can’t think of going on a birding trip without my recorder.” On a trip to Assam he recorded the call of a Streaked Spiderhunter, an experience he called “pure bliss!” “Listening to the birds”, Saify says, “works like a therapy….it just eases out the stress.” With recent travel restrictions, Saify has been recording birds from his home as well including this Coppersmith Barbet.

Natasza Fontaine says she has always listened to birds. “I guess I was a birder before really knowing what birding was,” says Fontaine. As a kid, Fontaine watched House Sparrows from her stoop and wondered what they were fighting about; “that curiosity”, Fontaine said, “never really left me.” Fontaine followed her curiosity to Queens College, City University of New York where she volunteered to work in Dr. David Lahti’s Lab with a master’s student studying Northern Mockingbird songs throughout Manhattan, the Bronx, and Westchester County. As soon as Fontaine started recording Northern Mockingbirds and other birds, “that was it; I was hooked,” she said. Recording, Fontaine says “became a huge motivation in my birding, it added another layer. I no longer wanted to only see a bird; I wanted to capture its essence through song.”

Recording a new species, Fontaine says, “is simply exciting.” “It’s a personal validation that I saw this bird AND I know what it sounds like.” Fontaine also enjoys the pleasure of knowing that the song she just recorded is going to look great when she sees the spectrogram. “Knowing that someone will find either purpose in the recording for their research or find personal satisfaction in using one of my recordings to help them ID a bird makes me happy and proud of my work,” says Fontaine.

COVID-19, however, has decreased Fontaine’s recording efforts because of the limited access to many parks and with that she says the safety decisions she needs to make as parks open. Fontaine also says that “the violence and discrimination against Black people have further decreased my recording efforts. As a Black birder, there are times I am faced with outdoor obstacles and, at this time, I feel the need to be more selective of where I bird. The pandemic, the disturbing political climate, including the ongoing racism, has taken a huge toll on my motivation. I cherish the recordings I am safely able to obtain. They are my personal gems in this time of distress.”

Sharon Glezen, a relatively new bird watcher from Vermont, said she hadn’t fully appreciated how much birding is done by ear until she started watching birds. Recording, Glezen says “often helps me later with identification,” but she adds that recording “simply adds to my memories of the time spent birding and helps to paint a more full picture of the experience.” Glezen says she enjoys being able to pick out each individual member of the orchestra, each voice in the chorus, and when she hears a particular song that she’s recently learned, the connections she says “creates pure joy.”

Initially Glezen says she was intimidated by recording, in part, because it seemed labor intensive, but when Glezen added her first recording to her eBird checklist she learned that it was actually quite easy. Glezen is spending more time watching birds around her home as a result of COVID-19 and is hoping to add more recordings to her checklists. “I have been grateful for this connection to the natural world, and for the incredible diversity of songs that surrounds us,” wrote Glezen.

Nick Athanas is a professional guide for an international birding tour company, but with stay-at-home orders in place, Athanas found himself with a lot of time on his hands. Athanas has added more than 2,500 recordings to the archive since March. “I’ve made a lot of progress, but still have several thousand more to get to,” wrote Athanas in an email. “It’s a lot of work adding thousands of recordings and photos, but I like knowing that birders and ornithologists will be able to enjoy them and derive scientific benefit out of them, now and hopefully long into the future.”

Athanas enjoys adding unique vocalizations to the collection such as the possible song of a Golden-crowned Tanager he recorded in Ecuador and recordings of species that were previously not in the archive such as the Rufous-headed Robin and Burmese Yuhina

Rachel Barham says she’s been recording birds for a while, but started archiving her recordings when she realized how valuable they are as a resource. Barham says, “I use the Macaulay Library all the time.”

Barham is a classically trained singer and as such owned a decent recording device, so when not singing she took to recording birds. “I’ve always enjoyed recording mockingbirds in different geographical areas. I am in awe of them, how accurate they can be, and I enjoy doing the detective work to figure out exactly which birds they’re imitating,” says Barham.

Barham says “when I put a catbird recording on, it took me instantly to early summer. I heard not only the bird I was recording on purpose, but all the background birds that aren’t there in December. It was such a delight to revisit that particular time and place, and it really made me think about the rich variety of birds that we take for granted during the singing season,” Barham wrote in an email. ”I love hearing field recordings in a different season because I hear everything equally on the recording, which is different from being in the field when I’m concentrating on a particular bird or two and ignoring the others. I even enjoy hearing the insects.”

Michael Taylor first got interested in audio recording to learn a few bird songs that often confounded him in the field, such as the “kwirr” of the Red-bellied Woodpecker and the “kweeah” of the Red-headed Woodpecker. Taylor took the Sound Recording Workshop in June 2018 and says, “I’ve been recording ever since, as time permits.” His focus has been on recording as many species as possible for his county in Bollinger, Missouri.

But Taylor notes that he has also started recording more frequently because of coronavirus. Taylor says, “when I’m not recording video lectures for my biology courses, I’m using my “shelter-in-place” time to record birds, either on my property or at a nearby hotspot.” Taylor says he’s been adding a lot of recordings because, “to paraphrase Macaulay Library collections manager Matt Medler, there is no such thing as a bad recording. If I’m going to point the microphone at a bird, I’m going to upload any usable audio to Macaulay Library. Even poor recordings might have some value. That’s why I’ve uploaded so many,” says Taylor.

One of Taylor’s recent and memorable recordings is of a Northern Mockingbird that he recorded in the parking lot of the hospital where his wife was having surgery on her broken ankle. Taylor was not allowed inside due to COVID-19 so, Taylor says, “I had to wait outside the hospital and to kill time between rain showers, I recorded.” This recording is also memorable to Taylor because it was the first recording he made with his new recorder (Sound Devices MixPre-3) and parabola (Telinga Universal Pro).

Mairi Connor grew up in the Highlands of Scotland, where she enjoyed watching birds, but when she moved to the city, she lost touch with the birds. Now Mairi has returned to the countryside where her love of birds has also returned. “I found my binoculars I’ve had since I was 15 and I haven’t put them down since,” says Connor. This spring Connor discovered 38 birds in her garden and started paying attention to the sounds of each species. “I love that now I can make recordings with my phone and I can refer back to them whenever I want to help me learn bird songs and calls. I love that I can shut my eyes and listen to the birds and know which bird it is just by its song or call,” says Connor. Birds, Connor says, “make me very happy and my husband always says I have a goofy smile on my face when I am watching and listening to the birds, so having a recording of their beautiful songs is an added bonus.”

Daniel Mok is new to birding as of January 2020 and as he writes on his eBird profile “I am totally in love with it. I thought I was more of a reptile and fish enthusiast, but birds are honestly just as fascinating!” Mok started recording birds as a result of an assignment in college. “My favourite thing about recording,” Mok says, “is viewing the spectrograms they produce. I find it fascinating that birds are able to produce such complex songs filled with amazing vocal athleticism. The best part is that it’s so accessible. I do my recordings on my phone.”

Recording bird vocalizations is a wonderful experience as these and other recordists can attest to. If you are interested in getting started check out our resources and tips.

Thank you to all of the recordists who have archived audio recordings with their eBird checklists in the Macaulay Library. If you have a story to share about your experiences with recording bird songs, we would love to hear from you (MacaulayLibrary@cornell.edu).