Many avian species in North America differ in physical appearance, leading researchers to split them into separate subspecies, often based on geography. Just how subspecies form is a question many researchers are trying to answer: How do these physical and plumage differences arise? Do subspecies have behavioral differences, too, such as different songs? How do these differences alter the interactions between subspecies?

Early studies of bird song often explored various factors such as geographic boundaries or elevational differences, that can correspond to variation in songs within a species. Scientists call these variations song dialects, which are somewhat similar to different accents in human speech. Researchers have also described patterns of gradual differences in song across a species’ range, but these clinal patterns are less commonly observed as it is difficult to obtain songs from many field sites across a large geographic area.

In the Creanza Laboratory at Vanderbilt University, we study cultural evolution, or the changes that can accumulate over time and space by the process of learning a behavior, such as a song, generation by generation. In particular, we are interested in determining how existing data can be leveraged to conduct large-scale cultural analyses of bird song. Thus, we are thrilled that so many birders from across the globe are contributing their recordings of songs to public repositories like eBird and the Macaulay Library!

The wide geographic coverage of citizen-science data provides an excellent opportunity to determine if changes in song have accumulated over time for an entire species, allowing us to look for corresponding genetic differences in any subpopulations that differed in song.

For one “little brown bird,” the Chipping Sparrow, subspecies’ boundaries have been defined and redefined over the decades. However, these classifications were weakly supported by either physical or genetic differentiation between the proposed Eastern and Western groups.

To better understand subspecies boundaries and changes in song over space and time, we used the hundreds of recordings provided by citizen-scientists to Macaulay Library and Xeno-canto to study the simple song—one single repeated syllable—of the Chipping Sparrow. With such a short, predictable song, we are able to characterize the entire song repertoire of each Chipping Sparrow with one recording. We downloaded as many recordings as possible across the entire geographic range of the Chipping Sparrow, from northern Alaska to Guatemala, and added these to recordings collected by field scientists such as our collaborator Dr. Wan-chun Liu and those at the Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics.

For 820 Chipping Sparrows, we extracted and analyzed recordings with our new software—Chipper. Our team designed Chipper to rapidly detect and measure syllables, the core parts of a bird song, while minimizing the amount of adjustments needed from the user. The software was specifically designed to work with various species’ songs and on recordings collected with the different devices used by citizen-scientists. See how it works in our YouTube video.

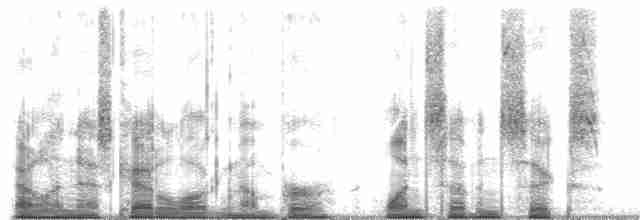

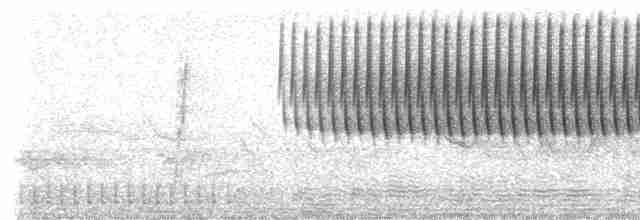

From our analysis of these syllables, we were able to detect interesting differences in songs between eastern and western Chipping Sparrows. The Chipping Sparrows in eastern US/Canada sing songs with fewer, longer syllables compared to the western birds. In other words, eastern and western Chipping Sparrow songs were about the same duration, but the western birds sang faster-paced songs with more syllables.

If you listen to an “average” song of each of these subpopulations, you can see and even hear the difference! However, there is a lot of overlap between the populations, too—we don’t know for sure whether an individual Chipping Sparrow is from the eastern or western US/Canada just by looking at its song (see our paper for data visualization). So, without knowing the location, it would be very difficult to tell whether a Chipping Sparrow you heard singing was from the eastern or western United States. When we look at many songs together, though, a geographic pattern emerges.

Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina

Chipping Sparrow Spizella passerina

Although we found a geographic pattern, we did not find significant genetic differences between the eastern and western populations of Chipping Sparrows. There are detectable song differences between these two regions, but these differences do not correspond to two genetically distinguishable subpopulations. It is possible that eastern and western Chipping Sparrows have not been separated long enough to accumulate genetic differences but their songs are capturing this separation in progress. Field studies could better test this new hypothesis.

Even so, we should keep an eye on these song differences! As sound collections continue to grow over the years, it will be worthwhile to revisit this research to see if the populations’ songs diverge even further with time.

Since our song coverage from citizen-scientists spanned the entire continental United States, we also tried to determine if the differences in song that we were observing have a clinal pattern that gradually changes with longitude. Some of our results suggest that this is indeed the case. However, the number of recordings from the middle of the U.S. are limited, and our findings could be strengthened with additional recordings collected by you!

The Chipping Sparrows’ migratory behavior, while understudied, is also interesting to consider as a possible contributing factor to cultural divergence: most Chipping Sparrows migrate north up the eastern and western sides of the US/Canada, but some remain sedentary in Mexico and Central America. This made us curious about the songs of the southern birds: do they differ substantially from those that migrated north? If so, could these songs contribute to genetic differentiation between the migratory and sedentary populations?

Unfortunately, there were too few songs collected from the southern population of Chipping Sparrows to make any significant conclusions. If you have recordings of Chipping Sparrows from the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America, please consider adding them to the archive with an eBird checklist. Or, if you live in these undersampled areas, don’t forget to add a little brown bird—the Chipping Sparrow—to your list of species to record on your next bird walk!

Read the paper:

Searfoss, A. M., W.-c., Liu, and N. Creanza (2020). Geographically well-distributed citizen science data reveals range-wide variation in the Chipping Sparrow’s simple song. Animal Behaviour: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.12.012

Abigail Searfoss, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University

Nicole Creanza, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University