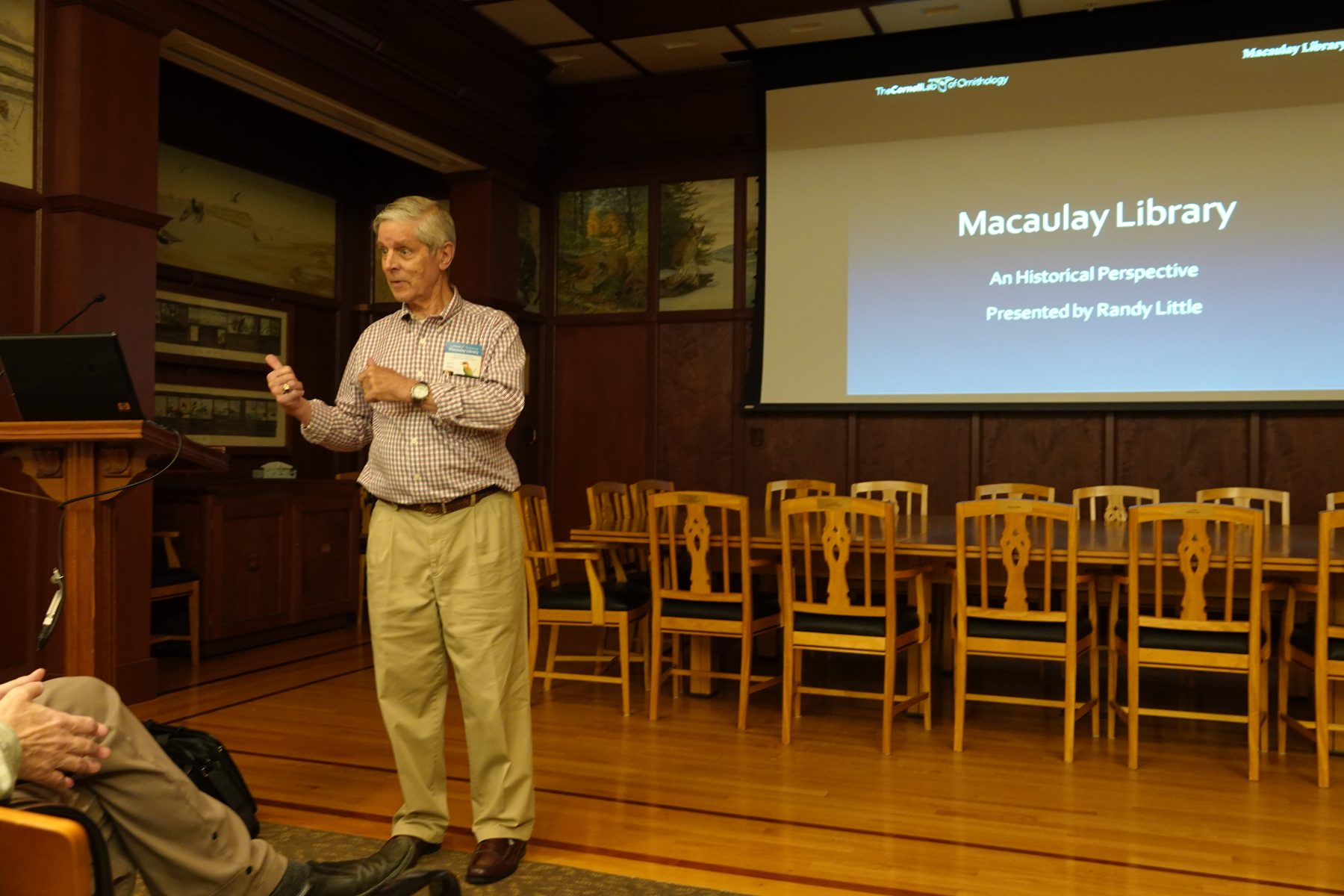

Randolph Scott Little grew up surrounded by giants. His elementary school stood in the shadows of Fernow Hall on the Cornell Campus, then the home of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. After school Little would walk up the hill and tug at the shirt sleeves of Arthur Allen and Peter Paul Kellogg, the founders of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Little was fascinated by what he saw and wanted to help them do anything and everything.

“Observing the colorful plumages of stuffed hummingbirds in a display case in Fernow Hall may have been what kindled my lifelong interest in birds,” wrote Little in an essay about his childhood home. “Not the hummingbirds themselves, Little says, but the welcoming words of Dr. Arthur A. “Doc” Allen who saw my interest and invited me to return and explore further whenever I liked.”

The young Little returned to Fernow Hall day after day seeking to learn as much as possible and Allen and Kellogg weren’t shy about putting him to work. Little had a knack for finding bird nests—a match made in heaven for Allen who was keen on photographing birds and nests. Little scoured the neighborhoods for nests as much as he could and provided Allen with many photography opportunities.

Little also served as Doc’s “go-awayster,” a fun story Little enjoys telling. In 1932 Allen discovered that the deep resonant sounds of the Ruffed Grouse came from them beating their wings against the air. But as technologies advanced Allen really wanted to film a grouse drumming. Allen attempted to film the bird from a blind, but Allen noticed that the grouse seemed skittish when he was in the blind because, Allen surmised, the bird knew there was a person in there. So, Allen asked Little to follow him into the blind and leave the blind once he was all set up, serving as Doc’s “go-awayster.” The grouse, sensing that nobody was in the blind, returned to normal behavior and Allen was able to document its behavior on film—a first in the study of animal behavior.

Finding bird nests and helping Doc with his projects was great fun for Little, but when Kellogg asked him to help aim the large parabolic microphone, Little was thrilled. Back in the day it took two people to record bird sounds, one person to crank the recorder and one person to hold the parabolic microphone. Little loved aiming the microphone and found recording birds to be super satisfying and that, Little says, is how his recording career got started.

Despite being steeped in ornithology, Little’s career isn’t in ornithology. When it came time for Little to go to college, Kellogg told Little not to bother taking ornithology because he already knew everything. Instead Kellogg told Little to study electrical engineering if he really wanted to advance the field of sound recording. Little heeded Kellogg’s advice and studied electrical engineering at Cornell. He then went on to have a 37-year career at Bell Telephone Laboratories and AT&T Headquarters. A fulltime job and a new family meant that Little didn’t get much time in the field recording, especially early on at Bell Labs. But whenever the chance presented itself, Little was game to get out in the field and record birds.

During college Little worked at the Library of Natural Sounds (now the Macaulay Library) keeping the equipment in shape and helping master vinyl records of bird sounds, the sales of which helped support the Lab. When school was out of session, Little headed out in the field at every opportunity to get recordings of species missing from the archive. He even built his own recording unit, an Eico kit tape recorder to record birds around his home.

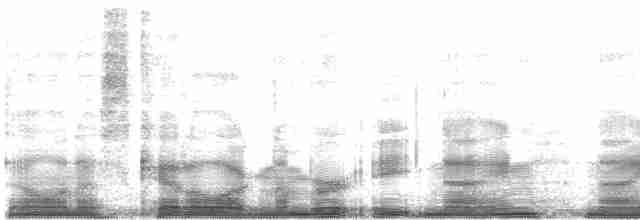

In 1961 Little was in the Rocky Mountains recording birds for Peterson’s guide to bird sounds with a Nagra III-B tape recorder, which was one of the first recorders that allowed one person to handle both the recorder and microphone.

American Dipper (Northern) Cinclus mexicanus [mexicanus Group]

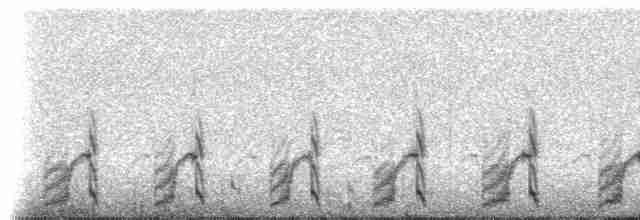

Those recordings with a portable recording unit were memorable for Little, but perhaps the most memorable recording, Little says, took place on Baffin Island, Canada. William “Bill” Gunn, a renowned recordist, wanted to publish a collection of the sounds of North American shorebirds and one of the last recordings Gunn needed for his collection was a Common Ringed Plover in North America. Gunn called upon Little to help him with the last recording. Little jumped at the opportunity to join Gunn in the field, but Gunn’s health was deteriorating, so Little headed to the arctic alone to get the coveted recording. On the first flight up to Baffin Island, Little only got as far as Frobisher Bay. The second flight took him to Baffin Island, but it took three attempts to actually land the plane due to weather. Finally, Little made it to Baffin, but the weather was still miserable with strong winds blowing across the treeless tundra. Little spent several days out on the tundra trying to get a recording of the Common Ringed Plover with little success. On the very last day at the last minute before his plane was about to leave Little heard a Common Ringed Plover flying overhead. He started recording immediately when a second plover circled in and landed near the rock shelter he built early. He scurried back to the rock shelter and recorded a pair of Common Ringed Plovers in the nick of time. “Holy cow, how lucky can you be,” said Little as he hurried back to catch his plane.

Little’s passion for sound recording isn’t just about getting the recordings, he also wants to pass along his knowledge and passion for recording to others. He began passing on what he learned from Kellogg and his own experiences at the annual Macaulay Library sound recording workshops. Little taught his first workshop in 1987 and continued to help teach it for more than 30 years. And to this day Little still participates in the workshop—he never lets a teaching moment slip by him. Little says, “just because you can hear a bird doesn’t mean you can make a decent recording of it. You need to train your ear to think like a microphone. How loud is the signal relative to the background noise? Most people’s first recording attempt is like taking a snapshot, but it’s nothing to write home about. Learn to listen like a microphone.”

I asked Little if he had any other advice to pass on to fellow recordists. Without skipping a beat, Little says, metadata, the information added to each recording that tells others more about what was going on during the recording, like behavior of the bird, its gender, and habitat. “A recording without metadata is not very valuable, but even a poor-quality recording with metadata can be quite useful,” say Little. “Oh and carry a notebook,” Little says, even if you get made fun of for carrying one like he did. It’s good practice to take notes, says Little.

Little is a truly dedicated recordist with 2,014 recordings and counting in the archive. The first solo recording he archived in the Macaulay Library was in 1959 and he continues to archive recordings today. That’s 60 years of recording—an achievement that is unmatched in the archive’s history.

Little’s involvement with the Cornell Lab and Macaulay Library doesn’t end with sound recording; Little served on the steering committee for the Library of Natural Sounds and the Cornell Lab’s administrative board from 1998 to 2011. Little says his proudest accomplishment was helping rebuild the academic capacity of the Lab of Ornithology.

Little also serves as the unofficial historian of the Lab. He has been at the Lab practically from the beginning and continues to share his knowledge and passion about the Lab with the world. Little self-published a book about the Lab’s history in 2003 called “For the Birds: Cornell Lab of Ornithology at Sapsucker Woods,” an entertaining and informative read full of personal narratives and history.

It seems fitting to end Randy’s story with his signature email closing, Good recording. Thank you, Randy Little for your commitment to the Cornell Lab and the Macaulay Library!

Listen to more of Little’s recordings.